The wheels of my Cessna 210, Charlie Golf Papa Lima Sierra, gently lifted off the runway, and I was airborne. I put the gear handle up, and my Cessna did it’s typical wiggle-waggle dance, tucking it’s wheels in cleanly, going from an awkward duck to a sleek and clean heron. It’s one characteristic of the 210 that I love, where the airframe gives you it’s nod of approval that the wheels are tucked, we’re cleaned up and ready for this adventure. As I continued the climb, the runway dropped beneath and behind me, and gave way to the sugar sand beach of St. Barth’s Gustav III runway 28 threshold, made famous by landing overruns and clouds of sand from spinning props as failed landing attempts end in bent airplanes and broken egos. I continued the climb over the beach, turning to 60 degrees by Eden Rock, and grabbed a deep breath. It brought me back to my first solo in 1999, and it hit me just like it did then: Now I have to land this thing – preferably on runway 10 at St. Barths. The journey to get to this moment has been 22 years in the making, and I was about to check off a very significant item from my Aviation Bucket List (ABL).

This particular trip started on December 26. It had initially been planned for a year prior, but we all know what upended that one. The pandemic has created more hassle, paperwork, and inconvenience than one could possibly imagine, but holding a private pilot’s license has been a Godsend to this hopelessly restless prairie boy. It’s a luxury and a privilege that I did not for once take for granted – when most people were stuck on the ground in isolation, I could get up in the sky and keep my perspective on life, breathe some fresh air, experience some semblance of freedom, and maintain my sanity. We had been planning this trip as family for almost 2 years, since the last time we flew to the Bahamas, and between juggling Covid restrictions and business commitments, we were pretty determined to make this one happen. Travel in the time of Covid was definitely not for the faint of heart, it took solid commitment and determination, good scheduling, lots of time, and quite a bit of money. We found out first hand how a lack of any of these could quickly derail the best laid plans. Our plan was initially pretty simple: I would fly down to Bahamas in the 210 with my two sons, and my wife would fly commercial with our 2 daughters (our family is just getting a bit too big to take all of us plus luggage). We would vacation with our family in the Bahamas, send all four kids home commercially after 10 days, and continue on to Sint Maarten with some friends who would fly in to Nassau to join us. All told we planned to be away around a month or so. The journey down through the U.S. was pretty uneventful, with the only IMC conditions I had to deal with on our first landing in Fargo, North Dakota for customs. My TKS weeping wing system made short work of some moderate rime ice as we made the approach into KFAR. Customs in Fargo was pleasant as usual – it’s so pleasant that I will fly out of my way to do customs there on a regular basis. We pushed pretty hard that day, and after 4 legs for a total of 9 hours flight time, we landed in the dark in St. Augustine, Florida. The next day would be an easy one, with only one flight down to KFXE, Fort Lauderdale.

As far as private pilots go, I think I’ve done my fair share of over-water flight. I’ve flown to the Bahamas several times, but that kind of seems like cheating – warm water, boats almost always in sight, the U.S. Coast Guard nearby and if you’re not within gliding distance of land, you’re not far off from being able to. Now real overwater flying, a la North Atlantic, is also something I have a small bit of experience with. In 2018 together with my flight instructor, Luke Penner, we completed a transatlantic crossing to Europe and back, also with this same airplane. We put a lot of time and effort into our preparation, taking an underwater egress course, wearing full immersion suits and inflatable vests, carrying an Epirb and satphone, and also bringing along a self-inflating emergency raft. The raft I had purchased for that trip was fairly specific to this kind of mission, and altogether with the survival gear it contained, weighed about 75 lbs. This kind of mission, being that it’s over warm water, shorter flights, in reasonable range from search and rescue crews, I decided I wanted to find something smaller and probably easier to deploy. The decision was made to buy a new raft, albeit one much simpler, smaller, lighter, and hopefully more manageable for my family to deploy should the need arise. I’ve done quite a bit of studying, reading, considering, and thinking about ocean ditching, and to be honest I’m still unsure how feasible it would be to deploy a raft following a water landing. I hope I never have to find out. We made our stop at Banyan’s Pilot Shop, the largest in the world. I left with a new, lighter raft, and a much lighter wallet. Pilot Shops will do that to us piloty type folk.

The next day, I loaded up with my boys, and we launched east over the water. KFXE, Fort Lauderdale Executive, is a really nice airport and friendly to GA traffic. The corporate jets come and go and mix with us lowly piston-prop people quite nicely. I’ve taken off from KFXE for the Bahamas a few times, and it came pretty natural to me to lift off of runway 09, set climb power, and watch the coast of Florida slide beneath us as we turned toward Nassau. My wife and our daughters had taken off from Toronto on Westjet Flight 2754 about an hour prior, so as we settled into our final cruise altitude of 11,000’ and out of curiosity I tried to find their flight on my traffic display. No joy, but I knew that the timing should work out pretty good, as we would arrive about an hour before they would. The 162 nautical mile flight from Fort Lauderdale to Nassau went by quickly. Total time was scheduled to be about an hour. But the scenery was changing: from the lush green of the Florida Everglades to the dark deep blue Atlantic, finally giving way to the aqua, turquoise, and white sands of the Bahamas. I was cleared for the visual on runway 10 at Lynden Pindling International, and after only an hour, had landed in paradise.

We spent the next 10 days holidaying with our kids, in and around Nassau for a few days, then on to Spanish Wells. We thoroughly enjoy all the Bahamas has to offer for family vacations and it has become a place we all treasure. With our kids either just entering or just prior to entering adulthood, these holidays are special to us, and we know that these special times may become limited in the future as they move on to careers and new families. On January 8th, I flew our kids back to Nassau and they caught their jet home, back to the Great White North, and sub-minus-30c temperatures. But the aviation adventure had just begun.

After I dropped off the kids we picked up some friends who had flown in from Manitoba, and our holiday was going to enter phase two. All along, the goal for this holiday was not only to kick back and relax and enjoy the warm weather and scenery – it was part flycation. I wanted to stretch my aviation wings and venture beyond familiar frontiers. I had St. Martin, Princess Juliana Airport (TNCM) as one of my bucket list destinations. And I had also heard about other alluring destinations like the Dominican Republic, Saba, and St. Barths. We were a little unsure of how much hassle Covid was going to cause, and we weren’t sure how much time we really wanted to spend jammed into a Cessna. But as I sensed just how close we were to ticking off some of these places from my bucket list, I knew it could be now or never, and I had to go for it. It took less effort than I had thought to convince my travelling companions, and no one was worked up about flying over water, out of gliding range from land. We were all mentally prepared, briefed, trained, and ready. I got serious about planning and preparation, which to a large extent meant figuring out what the protocol would be regarding Covid tests, pre-entry travel health visas, Covid health insurance, and covid related customs procedures. Every country was different and everyone had different requirements or procedures. It generally would take an entire evening per country to fill out all the right online forms and get all our vaccination and test data uploaded to their various portals. It was pretty cumbersome and somewhat onerous and repetitive.

Meanwhile, in the back of my mind, YouTube videos of airplanes landing in St. Barths were on repeat. I had heard about this unique airstrip before – one member of our flying club at home had flown there from St. Martin with a rented aircraft a flight instructor years prior. His story captivated me, and I never forgot it. I read up about it, learning that certification is required to land there, and I watched the YouTube videos to imagine how my 210 would handle that approach. I had to find out if I could do it, and add that certification notch to my aviation belt. Between filling out forms and figuring out where we could get just the right Covid test in just the right timeframe, I began to search for certification training providers for landing at St. Barths. I quickly found the St. Martin Aeroclub, based at Grand Case Airport (TFFG), on the French side of St. Martin. I sent an email and got a reply within a day, and confirmed that training would be available in the right timeframe. I booked it and we had our final destination for our Caribbean journey firmly in sight. We stopped for three days in Samana, Dominican Republic, and on January 15, flew to one of the places I had always dreamt of flying to, making that epic approach over Maho Beach, gracing the tourists on the beach below. We landed at Princess Juliana Airport, Dutch Sint Maarten.

The flight from El Catey (MDCY) in the Dominican Republic, to Sint Maarten was fascinating and uneventful – barely. Prior to departure I had religiously checked weather, airspace, and NOTAMS. There was an interesting NOTAM for TNCM referencing “slow control” and to expect delays. I wasn’t quite sure what to make of it, but it didn’t say we couldn’t land. I filed my flight plan and we departed over Samana Bay, crossing over to Puerto Rico, following the north coast. Then over the U.S. and British Virgin Islands, places that had been so foreign and intriguing to me. We were just passing over the island of St. Thomas when San Juan Approach handed me off to Miami Centre.

“Charlie Golf Papa Lima Sierra, Miami Center”.

“Charlie Golf Papa Lima Sierra, go ahead”.

“Charlie Golf Papa Lima Sierra, make slowest safe speed, expect holding ahead. ATC advises slow control at Sint Maarten”.

Huh? What the heck is “slow control”? I had read the NOTAMS during my flight planning process and had noticed one referring to this, but it didn’t say I couldn’t land and surely my “handler” was taking care of any advance notice, as they had assured me. Further instruction from ATC advised to adjust my speed to increase my ETE by 17 minutes. I slowed my airplane down to a really low cruise speed, taking it about 40 knots down, but that didn’t net me 17 minutes, more like 6. We continued on for a few minutes as I wondered what they were going to say next. I mentally started to brief myself on holding entries and looking ahead on my route for a holding fix. Sure enough, the instruction came. Miami Center gave me a fix 30 degrees away from my intended destination and advised to hold. I set the course and the autopilot made the turn, and started to process this. I was being sent to hold over a point that would take me away from the shortest route to land or an airport, in a single-engine-piston-airplane, with passengers on board. I’m all about taking necessary calculated risks, but I also think that we should minimize them every chance we get, realistically. To me, this was adding unnecessary risk, not reducing it. I started thinking about this from a very practical perspective: We were in blue-sky VMC, not with bingo fuel but definitely not with full tanks. My passengers are a little ancy, you’re asking me to add a bit of risk to my flight, and I don’t really know why. I pulled a trick out of my bag that I’d used before: Cancel IFR. I’ve been in this situation before where the only reason I’m being asked to do something is to maintain IFR separation, and if the conditions present less risk for me to do that, maybe it’s a good idea to take that on. I called up Miami Center and canceled IFR, and I was dumped off quicker than a windsock flap on a gusty day.

“Papa Lima Sierra squawk VFR, change of frequency approved, good day”.

I was on my own, over water, heading to an airport that had something going on that I didn’t know about. But in my mind, I had already decided I’d rather fly circles around the island, near land and people and civilization, than some imaginary point 80 miles over water from anything. This was the risk I was prepared to take.

We bombed on toward TNCM. I called up Juliana Approach Control and without issue was given vector instructions to enter the approach path. The controller was friendly and helpful, even welcoming. I lined up for runway 10, and had Maho Beach in my sight. It was exciting and exhilarating to be so close to making the approach I had dreamt about for years. We descended on the glide path, and I soaked it all in. Over the beach I could see the spotters and sun tanners and swimmers, and even saw a few big waves out of the corner of my eye as I honed in on the threshold. With three signature “chirps” of my tires on the runway, we had landed at Princess Juliana Airport, and I had checked off one more thing from my bucket list.

It was busy on the ground, with airliners taxiing to and from their gates and commuters zipping about. With no dedicated ground control frequency, there was a bit of confusion as we looked for a place to park. Finally a marshall came to lead us and we headed for a nearby Airbus A330. We parked under the wing. It seemed fitting that after an epic approach, we’d be given an epic parking spot for our little Cessna. We were greeted by a friendly face from Atlantic Aviation, and quickly to chatting about the approach and ATC. I mentioned my surprise at how things had gone, and he started to chuckle.

“Oh sir, that’s because there’s a strike today! None of the regular controllers came to work so all the managers are working. They are trying very hard to get all the planes in”.

Finally, I had my explanation for the confusion! I rolled my eyes at the silliness of it, but at least I now knew what was going on behind the scenes. It did frustrate me a little, and still does now that I was sent to hold, in a single-engine-piston-cessna, over water, unnecessarily. But I suppose the argument can be made that if I’m not comfortable doing that I shouldn’t be flying over water. I suppose it all isn’t as big of a deal if you do it all the time.

We loved St. Martin/Sint Maarten. It’s a really unique place – Caribbean weather, beaches, and culture meets European influence and flair. Opportunities abound for sunning on the beach, playing in the water, and sampling culinary delights. Nearly every flavor of food you can imagine is represented in the local gastronomic scene. Another definitely unique aspect of this island is the split between French and Dutch, with France governing the north half of the island and The Netherlands the south. Interestingly, there’s no customs or immigration requirement if you drive from one side to the other, however if you fly or sail, customs and immigration applies every time. We based ourselves on the French side near the Grand Case Airport (TFFG), where I relocated the 210 to shortly after we arrived. I had already made my arrangements with Aeroclub St. Martin, and had an instructor booked. I was this close now, I wasn’t about to pass up the opportunity: I was going to get my certification to land at St. Barth’s.

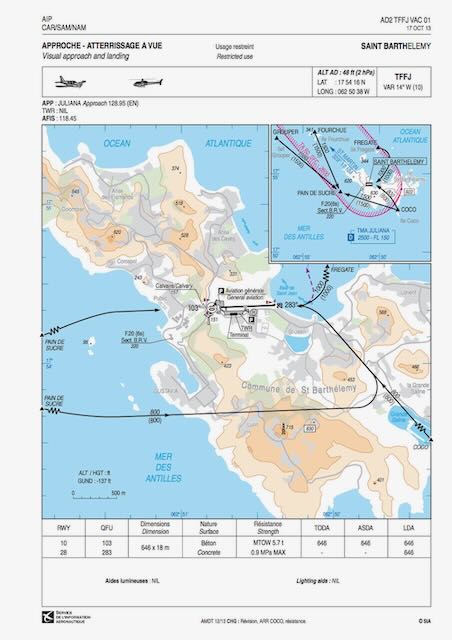

The Gustaf III Airport, TFFJ, or just “St. Barth’s” as it’s most commonly known, serves the playground of the rich and famous on the island of St. Barthelemy. But it’s better known, at least in aviation circles, for it’s iconic, unique, and challenging approaches. Most well known is the approach to runway 10, which brings the aircraft down a 6% glide slope, between two mountains, over a traffic circle, down a grass hill with a final descent gradient of 17%, with touchdown on a downsloping runway. On top of this, St. Barth’s is known for it’s shifting, gusty winds that can knock the most stable approach off it’s rockers. This airport is tidy and beautiful, and presents incredible opportunities for plane spotting, with numerous and some notorious YouTube videos to show for it.

My training was set and I was eager and ready to take on this new challenge. I had come so far – almost 3000 nautical miles – and I wasn’t about to pass up this opportunity. I met my instructor at the Aeroclub, and we sat down to review the airport and the special procedures required to land there. Training is fairly straightforward: Two hours of ground instruction, followed by enough flight time with an instructor to accomplish a total of ten landings, one of which must be on Runway 28, and missed approaches for each runway from various approach points. My instructor told me from the outset that I should set aside 3 mornings for this training, as it normally takes a minimum of 2 flights and often 3 before a pilot is signed off. We went through the ground presentation which gave an excellent written and pictorial description of the procedures. With no radar, in a mountainous environment, and a runway threshold with an obstructed view to traffic on final, mandatory reporting points are a necessity and good radio communication with “St. Barthelemy Info” (the French version of the Canadian Mandatory Frequency), are critically essential. We thoroughly went through a lot of material. The mandatory reporting points were one thing, but local landmarks were another. Watch for this green roof, then descend to this red roof, turn at the blue roof. Watch the moored sailboats to indicate the wind direction, then anticipate and compensate – this would come to bite me later. We wrapped up the ground work and headed out to the airplane for my first training flight.

The approach to runway 10 is the most well known, and for good reason. Entry points are either of the islands of Forchue or Grouper. Either of these will orient you to be coming in from the northwest, which is typical, as if you were coming from St. Martin. The islands are easy to identify, and with modern glass panel and moving map technology, simple to navigate to. But it’s just easier when there’s someone in the cockpit with you to help you sort it all out. A report over one of these islands gets you in touch with St. Barth Info, and then it’s direct to Sugarloaf Mountain, another island that acts as the final approach point to turn toward runway 10. In my airplane, I needed to be configured to land, with gear down, prop set to fine pitch, and flaps at 20 degrees just prior to Sugarloaf. At Sugarloaf, if the wind is fairly straight down the runway, you make the turn to the approximate threshold, which you cannot see. If the wind is northerly, you pass beyond Sugarloaf, extending the base leg a little further, and then turn to the runway with a slightly angled approach. The approach is now well under way, and here is where airspeed becomes critical. We picked a good approach speed to try, something I would typically use on a 3% glide slope – 90 knots – for our first attempt. We knew this would be too fast and would almost certainly necessitate a go-around. From Sugarloaf, I got the approach finalized, and continued in. Right before the coast, flaps to 30 and final GUMPS check complete. Another mandatory reporting is necessary on short final, at a point approximately where the sea meets the island, where landing is about to occur momentarily, but you still cannot see the threshold or the runway numbers. This report is necessary to make sure that there is no traffic about to enter or depart the runway – because neither of those would be able to see you at that point in your approach either. From short final, things get busy and intense in short order. The traffic circle, which is busy with vehicles and pedestrians and tourists and planespotters, comes into view. The mountains on either side meet up here. Part way up each mountain slope there’s a windsock for final windchecks, but at this point all of your concentration is directed toward airspeed and glide path that it’s almost impossible to see them. Closing in on the traffic circle is another larger visual – a monument with a large white cross. The goal of the approach path is to be at the same altitude as the cross when over the traffic circle, a task harder to achieve than it would seem. Finally, over the traffic circle, at the altitude of the cross, the runway threshold comes into view, and the designator, 10, is in sight. Now is the time to cut the throttle to idle, push the nose down – instinctively it’s difficult to do. My 210 is a slippery, greasy beast of an airframe, and it loves to pick up speed in any nose-down attitude. But there’s only one way to get to the threshold, and with only 2119’ of downsloping runway in the crosshairs to land and get stopped on, time is of the essence to get there. I push the nose down, against all instinct, and we begin our rapid descent down the hill, with tufts of long grass waving in my downwash barely 20’ below my toes. Finally we cross the end of the runway, having picked up some airspeed, and I naturally flare over the numbers. Meanwhile my instructor is coaching, encouraging, and keeping an eye on the critical factors, mostly airspeed – be ready to go around. Making that decision is pretty simple. About 900’ down the runway is a taxiway on the right hand side. If you can touch down before the taxiway, continue the landing. If you float by it, go around. It’s that simple. My first attempt with the 90 knot approach speed yielded the results we expected… a touch down about 150’ beyond the taxiway. Full power is applied, gear comes up, flaps in stages. We are going around. It’s fairly simple to fly the circuit from this point. Just climb out to beach at the threshold of runway 28, make a left hand turn to the island of Fragete, and then back to Fourchue where it all began. The second attempt was better – we adjusted approach speed to 85 knots – I think I did touch down just a few feet before the taxiway, but a go around was initiated just to be safe. On attempt #3, approach speed down to 80 knots. Not 78, not 82 or 83, 80. 80 exactly. I immediately noticed the difference as I pulled back to flare. The airplane responded with lighter feedback to the yoke, and I could feel the pivot of the airframe just prior to the point of ballooning, which had come so easily and immediately in the prior approaches. This time I could feel it all the way through the flare to touchdown. Three greasy chirps, and immediately the flaps are retracted to reduce lift and get better braking action. Touchdown was nicely 200’ before the taxiway. I rolled out to the end of the runway, soaking in the view of the beach, watching a windsurfer cross the runway centerline about 200’ out. I had just landed my own airplane at St. Barth’s.

We did a few more full stop landings until I felt a little more comfortable, but every single approach was a challenge that forced me to focus on the critical factors and apply control inputs deliberately and with precision. After each landing I would catch my breath, wipe the sweat from my brow, dry my hands, and mentally clean my shorts. This was flying on a level I have never done before, demanding skills that I was developing and growing right at that very moment. We closed out our first training day having completed the ground school and around 8 approaches to runway 10 with 5 successful full stop landings. With prevailing trade winds usually out of the east, runway 10 is by far the most common approach, but occasionally runway 28 will be in use. For this reason training for the full procedures for runway 28 are a requirement for St. Barth’s certification. We flew two different left hand circuits for runway 28, one right hand. All of them are challenging, in some ways even more so than the chop-and-drop of runway 10. Each of these approaches follows various landmarks to get the aircraft pointed roughly toward Eden Rock, an outcropping of rock on the south end of Baie de Saint-Jean. It’s home to a resort that’s built on top, and sits about 20 degrees, 300’ off the extended centerline from runway 28. Once oriented toward Eden Rock, the approach needs to be stable, with the aircraft fully configured for landing. On reaching it, it is now time to decide if you are ready to commit to landing, because beyond it, a go-around is prohibited. The left hand circuit we did worked out well. I looked for the various colored roofs that are the guide points for descent, base, and final leg turns. I hit my marks, and was heading toward Eden Rock, fully configured, airspeed on the mark. This was going to be a go around, and so at the prescribed point, full power was applied, gear up, and flaps in stages. What I wasn’t prepared for, however, was the nearly 60 degree bank required to execute the missed approach and keep my aircraft away from the mountains ahead. My instructor calmly demonstrated how he had probably done this hundreds of times, encouraging me to bank more sharply, and get my machine moving back out to sea. It was everything I could do to execute the maneuver, going against all my instincts to bank so steep when so low and slow. But with 325 HP driving an 80” diameter prop beating faster than the speed of sound, my airplane did it’s usual thing climbing like a homesick angel. We made good for Forchue, and restarted another approach, this time for a right hand circuit. The same maneuver followed reaching the decision point at Eden Rock, but this time I was more ready for it, and enjoyed every moment of it. We had completed almost all of the air instruction required. I pointed the nose back to Grand Case airport at St. Martin, relieved.

The next day we launched around 9am for St. Barth’s. I expected another exhilarating flight with more practice. We did two approaches to runway 10 which both resulted full stop landings, no go arounds. I was really getting the hang of it now, easily putting the wheels down before the taxiway, not using the entire runway to get slowed up. The next requirement was to execute a full stop landing on runway 28. I chose the right hand circuit because I felt that it gave me better visibility of the approach, and a less sharp turn to final. The downside, as I found out, was having the wind at my back as I made that turn to final. My approach was configured nice. I had the airplane set up and stable as we followed the coastline, direct to Eden Rock. As we came close, things started to happen fast. I had my marks set out for me and started the turn, just beginning to pass Eden Rock. I knew that now I was committed to land, a go around was no longer an option. But in the turn I noticed it, and immediately knew what I had done wrong – I failed to compensate for the wind. My turn had started a little too late, and now I had been pushed off the centerline, encroaching in on the south coast. I had no option but to continue the approach, banking steeply to try to regain the centerline, but now with power off. Bank angle was critically on my mind. Without power, and a steep angle of bank, lift began to decay. The airplane was losing altitude quickly. I saw a windsurfer out of the corner of my eye, a few yards off the beach. I added power to keep the rate of sink from getting away on me. Back on the runway centerline now, but glide path is too low… The beach came up to greet my left wheel and a resultant bounce reported our arrival. The second landing was on the asphalt. I got the airplane gathered up, and began to clean up my own emotional distress. I had landed my airplane on the beach at St. Barth’s. It wasn’t pretty, but it was fine. It was gentle as far as touchdown bounces go, and I knew the airplane hadn’t suffered any damage. My ego was a little bruised for coming up short of the runway, and the words of my flight instructor back home rang in my ear immediately: “You gotta compensate for the wind, buddy. The wind!” Another aviation lesson was learned, but my day was far from over. As we rolled out, up toward the ramp, my instructor did that thing that has happened to all of us pilots. When it starts to happen, at first your not quite sure it’s really happening. There’s a bit of fidgeting, and their hand discreetly goes down toward the seat belt buckle. Then it clicks, and you audibly hear the sound that signals what is about to happen. You are about to go solo.

“You’re ready for this, go and do two full stop landings on runway 10”.

Well chris i don’t know what to say except that your liveing life to the fulest and making memoreis that will last a lifetime.

LikeLike